Faces of Us

Venue: Charlestown Gallery

Nevis, W.I.

Dates: January 13 - February 7, 2025

Type: Solo Exhibit

-

In "Faces of Us," I explore human connection through nine paintings and sixteen charcoal sketches, each originating from intimate photographic sessions at the Alexander Hamilton Museum in Nevis. The works employ two distinct techniques that capture different aspects of human presence: gestural charcoal sketches where faces emerge from atmospheric shadows, and oil paintings where bold brushwork and luminous color bring forward each subject's vital presence. The penetrating gazes and subtle half-smiles in pieces like the monochromatic charcoal portraits reveal vulnerability and strength in equal measure, while the paintings' layered colors—from deep sepias to vibrant crimsons—reflect the complexity of each individual.

While each portrait stands alone, together they form a unified whole. The interplay between detailed paintings and immediate, expressive charcoal works mirrors our own ways of seeing each other: sometimes in sharp focus, sometimes in fleeting glimpses, but always with the potential for recognition. Through these faces—some contemplative, others quietly joyful—we see not just individuals, but reflections of ourselves, our neighbors, our community. In a world that often emphasizes our differences, these portraits stand as testament to our shared humanity.

Inner Fabric

Venue: Gateway Regional Art Center

101 E Main St, Mt Sterling, KY 40353

Dates: October 2023

Type: Solo Exhibit

-

Three years ago, at the height of the pandemic, I set out to compose the signature work in this exhibition, The Raft Revisited, a multi-figural composition of those closest to me - namely, my studio model and family members.

Inspired by Théodore Géricault's Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819), I worked on a large canvas where the figures appear life-size in contemplation and isolation. While other formal comparisons emerged from my subconscious in the making, I departed from Géricault's sweeping composition and now direct the viewer's attention inward toward a different type of confinement.

In 2023, as I was completing The Raft Revisited, I researched, in greater depth, the making of the Raft of the Medusa and learned that the artist initially had a woman as part of a small family unit in at least two preparatory sketches. The written accounts of tragic events, recorded by two survivors, also included a woman among those left at sea.

That was Géricault's narrative, and his reasons for removing the woman from the final composition are now lost to time. Many scholars, including art historian and feminist critic Linda Nochlin, in her essay titled "Géricault, or the Absence of Women", have speculated on the topic, coming up with new narratives for us to consider.

I am fascinated not only with the structure and function of our bodies as is demonstrated in this exhibition titled Inner Fabric, but with that of narrative and how it impacts our understanding of works of art past and present.

-

Emily Elizabeth Goodman, Ph.D. © 2023

In her recent body of work, Inner Fabric, Christine Huskisson plays with the tension between the surface and what lies beneath. Huskisson’s use of painterly and gestural brush strokes, combined with her careful application of color and delineation of form call our attention to the material plane of her works, making us aware of not only what she is portraying but how. Moreover, beyond her formal investigations of the surface of her works, Huskisson’s paintings invite us to consider what lies beneath, beyond, and, even, before the figures she has portrayed. Drawing from art historical precedents, anatomical illustrations, and the psychology of facial expression, Huskisson depicts a variety of different figures with an attention to the depth beyond their outward appearance and the delineation of their forms.

Throughout Inner Fabric, Christine Huskisson plays with the tension between depth and surface through her engagement with the materiality of paint. Constructing a cadre of works that involve dense impasto and gestural brushstrokes, Huskisson creates literal depth through the textured application of paint. Not only does Huskisson illuminate the effort of painting through the physical plane of each work, but her pieces have an additional depth with regard to their sense of historicity. Huskisson draws on both the history of abstract and expressionist painting—using thick brushstrokes, heavy lines, and vibrant use of color—as well as the conventions of figurative academic painting. In several pieces, Huskisson’s attention to the delineation of the human form illustrates her careful study of her live models; her works thus align with a long tradition of figure drawing practices, the antecedents of which we can see in the sketch books of Old Masters like Michelangelo, Caravaggio, or Jacques Louis-David.

Huskisson is acutely aware of this tradition, even basing one of her works off of French Romantic painter Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa. In the work The Raft Revisited (2020-23), Huskisson arranges the figures in a pyramidal composition, with bodies intertwined and layered over one another, seated on a replica of Géricault’s wooden raft, awash in a sea of blue. In the bottom right hand corner, Huskisson has incorporated an outlined figure falling off the raft that mirrors the dying man at the center of Géricault’s painting. Like in Géricault’s original, Huskisson has varied the facial expressions of her figures to create almost a gradient of emotion as the eye moves along the sharp angles formed by the strewn bodies, much like Géricault did in his depiction of the shipwreck of the slave ship the Medusa.

Huskisson makes clear that her work draws upon—literally and figuratively—Géricault’s process, while adding a new dimension to the painting itself. Ultimately, while there are parallels between the two, Huskisson’s piece transforms Géricault’s composition into something altogether distinct, an image that focuses on 21st century women and children awash in a more metaphorical sea than the actual 19th century shipwreck. Her figures are calmer and more cerebral than the almost melodramatic figures in the original, appearing to be more subdued by their precarious placement upon a meager wooden raft. The largest figure—a woman of color wearing green and white polka dots, taken from a stencil—has the expression of stoic resignation to her plight, gazing over the edge at the outlined body with a look that resonates with the sense of grit and weathering, as if being adrift is only one struggle in a life that has been dogged by multiple challenges. In this way, Huskisson adds a new narrative depth, a new perspective in relation to the original, and again demonstrates the persistence of something beyond the surface. In remixing elements of this previous work, Huskisson is creating a sense of historical depth beyond simply what she has portrayed.

Moreover, Huskisson’s rumination on The Raft of the Medusa is not simply about what is presented Géricault’s final work, but rather is a fixation on the process behind his painting. Huskisson notes that she “researched, in greater depth, the making of the Raft of the Medusa and learned that the artist initially had a woman as part of a small family unit in at least two preparatory sketches. The written accounts of the tragic event, recorded by two survivors, also included a woman among those left at sea.“ By including an outline of a sketched form from Géricault’s painting, Huskisson carefully considers the depth of history within a given artwork, both with regard to drafting and to its relationship with its antecedents.

Huskisson’s interest in the depth of process and the history of artistic creation is also apparent in the anatomical attention she pays in her rendering of the human form. While she primarily works from live models, Huskisson recently added the her understanding of the mechanics and structures of the body by visiting the University of Kentucky cadaver lab. Like artists of the past, supplementing her study of the physical human form with an examination of its underlying structures transformed Huskisson’s painting practice. She notes: “you can see a progression from the portraits to the more painterly, weighted bodies - still full of life perhaps, but with greater awareness of mortality.” As a result of this experience, Huskisson has imbued human figures that she portrays throughout this entire series a greater sense of depth, grappling with the limits of their physical materiality.

While many of the works within this series were influenced by her experiences with anatomical dissection, she has created a specific set of works wherein Huskisson makes apparent on the surface the structures that underly the human body. For instance, in her piece Cadaver Series 1 (2023), Huskisson portrays a woman laying on her side, legs stacked one on top of the other, resting on some abstracted surface that her upper body is wrapped around, obscuring one arm. The arm that is visible, however, is not only clearly delineated, but it is, in a sense transparent, as Huskisson has carefully delineated the shoulder, arm and hand bones contained within. Similarly, in the second work from this series, Cadaver Series 2 (2023), the same figure appears from a different angle, this time seen from behind, rendering both arms partially visible and obscuring one leg that is bent and tucked beneath the other. In this work, Huskisson has carefully depicted the lower spine, pelvis, thigh and calf bones of the one outstretched leg. In both of these works, Huskisson has created a clear sense of tension between the abstract and painterly surface, the surface of the human body and the structures and processes that underly them both.

Huskisson’s interest in what lies within a person goes beyond her depiction of anatomical features; in most of the works of Inner Fabric, Huskisson demonstrates a deep desire to convey the internal psychology of her subjects. This is especially true of her serial portraits, including the works in her Spectra Series and Square Series, among others. In several of these works, Huskisson has focused in tightly on the heads and faces of her subjects, isolating them from the rest of their bodies and surroundings frequently in oversized portraits. In her highly gestural and painterly depictions of these figures, Huskisson pays careful attention to the subtle details of each sitter’s facial expression, capturing the slightest raise of an eyebrow, purse of a lip, or shift of the gaze. In so doing, Huskisson’s portraits highlight the interiority of each individual, even when these personages remain unnamed. In focusing so narrowly on the facial expressions, Huskisson points to the fact that while emotions may be demonstrated on the surface of the face, the internal psychology that led to such an expression are unattainable to an individual viewer. We may guess at what is underlying this particular appearance, but we will never fully be able to know.

Throughout these works, Christine Huskisson probes the relationship between surface and depth. She crafts her figures with a sense of physical and emotional interiority. She imbues her work with a sense of history, both in terms of narrative content as well as through her application of technique and process. All in all, the works in Inner Fabric, demonstrate a careful attention to how painting can open up multiple dimensions beyond the 2D plane of a picture’s surface.

Thresholds

Venue: Lexington Art League

209 Castlewood Dr, Lexington, KY 40505

Dates: June 30, 2023 – August 18, 2023

Type: Solo Exhibit

-

The works in this exhibition began by exploring - in paint - my relationship with water. I've always loved water as a place to alter your perception of the world - ears under, eyes closed and weightless. Willingly crossing that threshold is always gentle and even spiritual.

As I pushed on scale and materials, I realised that the act of painting itself also evoked an affective transformation in me. Waterborne #1 was initially composed with my regular studio model - her face resting just above calm water. When I manipulated the canvas to another angle, I saw a different threshold, perhaps one that was not quite so gentle - abundance, drought, and the constant moving between those states of anxiousness is, in fact, another relationship we have all come to have with water.

Auditory deprivation was the intent behind Waterborne #2. Yet, this painting also transformed under the subtle yet intense chromatic transition that Payne's Grey can elicit - the greying of her neck muscles spoke of suffocation and the look in her eyes as crossing another threshold entirely.

Waterborne #3 was the final painting in the series of large canvases, where pleasure and pain now emanate from the few oxygen bubbles still dangling in her nostrils - her mouth slightly pursed as a hopeful sign that the sinking is a willing choice and one she can arise out of at any moment.

The entire painting process - the paint, the broom-sized brushes, and the pigments physically moved me from one state of being to another to another; it changed my perception just as sinking into water has always done for me. The creation of this body of work moved me from contemplating material thresholds to immaterial ones, but more importantly, the ability to access what is in between.

While in the liminal space, we are no longer one thing and not yet quite the other. That is a place of great spirit and great inspiration where we are free and weightless.

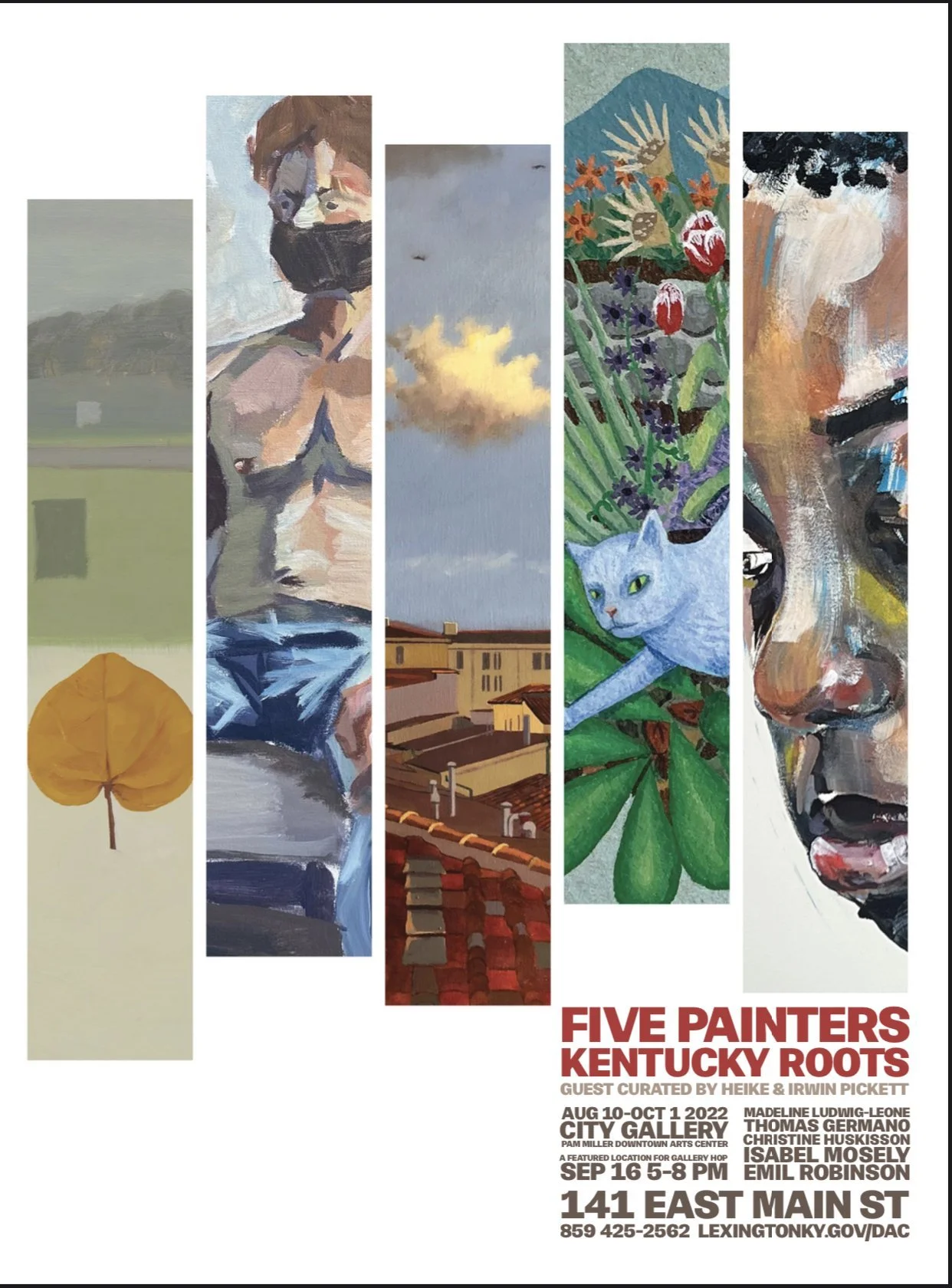

Five Painters: Kentucky Roots

Venue: City Gallery, Pam Miller Downtown Art Center

141 E Main St, Lexington, KY 40507

Dates: August 10, 2022 – October 1, 2022

Type: Group Exhibit